Until February...

/This is the final post for January.

Keepers #2 will be sent to supporters on Sunday, February 1st.

Regular posting will resume here Monday, February 2nd.

There's been renewed interest in the Alphablocks concept after I wrote about it earlier this month.

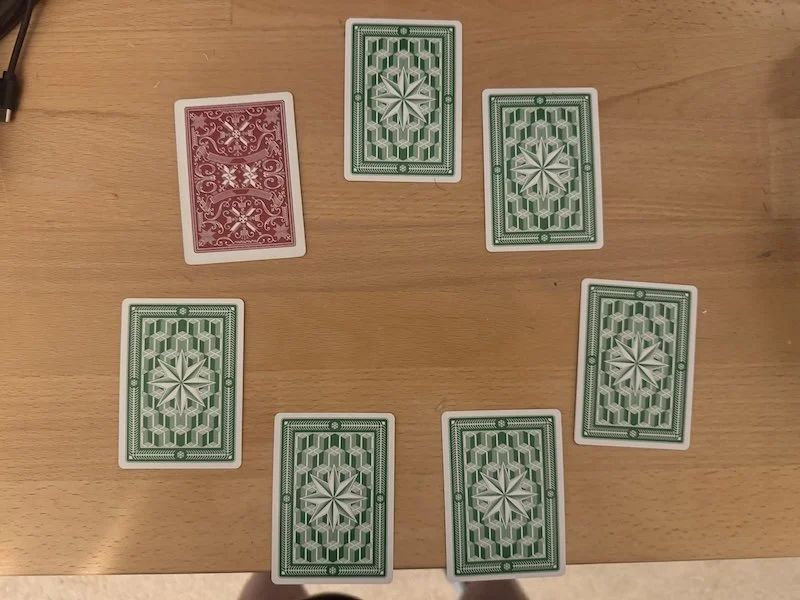

I'm not sure if I ever stated this explicitly, but the best generic framing for this process is "casting" Boggle dice or Scrabble tiles. Similar to "casting" runes, this is framed as a more modern process using these game pieces.

I do it over the phone as I test out this weird technique I read about. They're thinking of a word from their favorite song or poem or whatever. I "cast" a handful of Scrabble tiles and tell them which ones are face up. And they tell me if any letters are accurate. (They don't actually tell me what those letters are.) We try again and see how accurate the letters are.

We try one last time: "Wait, that's wild. They're all face up. Okay, so we have a B… wait… hold on. This actually spells something." I then take a picture of the "random" letters that just came up, and they spell the exact word they're thinking of.

Of course, I'm just finding the letters to spell their word once I know what it is. But the sound of Scrabble tiles or Boggle dice being shaken up is so distinctive that it paints the scene in their mind. And if I find the letters to spell their word before shaking and dropping a different group of letters, they strongly associate the picture I send with the sound they just heard—creating the illusion that the letters in the picture are the ones that just hit the table.

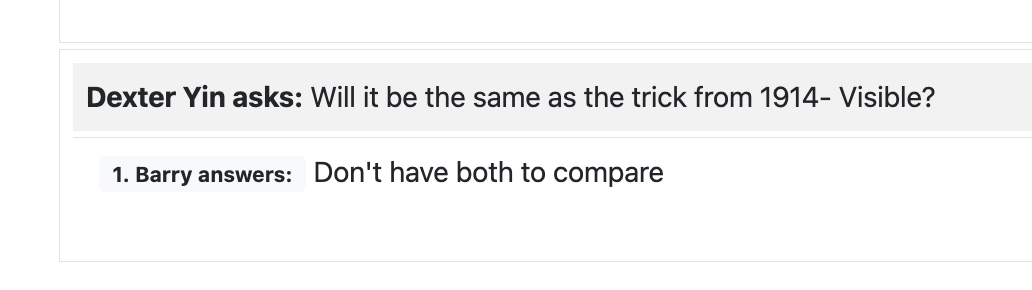

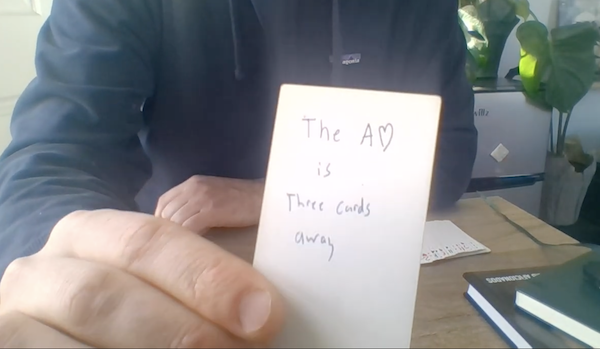

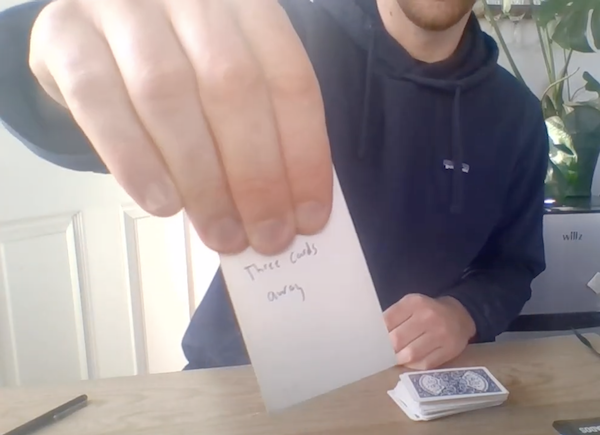

Vanishing Inc. features a Community Questions section on their product pages, which is a helpful way for people to ask and answer questions about individual products.

For example, on the product page for "Coincidenc3," Dexter Yin has a question and Barry chimes in with this helpful information.

Now, just so you understand, Josh and Andi don't come to your house at gunpoint and make you answer questions on the product page. This was Barry going out of his way to answer the question.

It's a weird way to go through life—feeling compelled to contribute your two cents when your account balance is literally zero.

Priest: If anyone here knows of any reason why these two should not be joined in marriage, speak now or forever hold your peace.

Barry: [Slowly stands.] Yeah, so I just want to say I don't know any reason they shouldn't be married. [Sits, then stands quickly.] To be clear, I don't know Steve and… Angela? I thought I was coming into a real estate seminar.

See you all back here in February, my little Valentines.