Fat Fuck Bloodhound

/Imagine

This weekend, I went to a rec-league basketball game for kids aged 6-11 with my friend Eric. You might consider this an odd, if not downright creepy, thing for two childless middle-aged men to do but… well… there is no but there, I guess. It’s definitely a little odd. But our motivation is pure. And it’s not like I’m standing behind a pillar, pressing my genitals up against it and taking creep-shots of the kids. We don’t hide our presence. In fact, we’re probably the most noticeable people there. With shouts of “Let’s GOOOOOO!” and some G-rated trash-talk, we’re hard to miss.

Really it’s just an excuse to get together, eat some deliciously-garbage concession stand pizza, and bet $100 on a game of 8-year-olds chucking airballs.

So, it’s Saturday, I’m sitting on the back-row of the bleachers with Eric, and he goes to grab some snacks. He asks if I want anything. I tell him to get me a pack of peanut M&Ms.

When he returns, I tell him I want to try something and I ask him to hold out the M&Ms. I bend toward the bag and inhale deeply, eyes closed. Not just a quick whiff, but a long intake of air. (Picture Josh inhaling the scent of Andi’s boxer-briefs after he just jogged a 10k for charity.)

I pull back. Look up. Tilt my head left, then right, as if I’m calculating.

“I haven’t done this since I was a kid,” I say. “They may have changed some stuff around.”

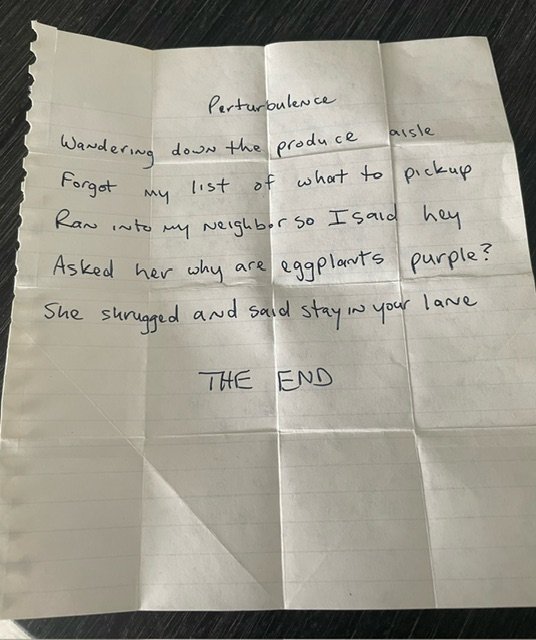

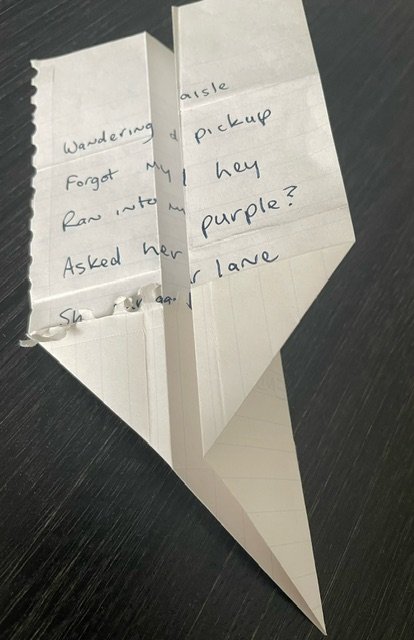

I reach into my messenger bag and pull out a pencil and a piece of junk mail. On the back of the envelope I start writing something. Then I pause, have him hold up the peanut M&Ms again and take another big inhale.

“I think I’ll be close,” I say and finish writing on the envelope. I hand the pencil to Eric to initial the envelope.

I unfold a napkin and put it on the bench between us.

“Dump them out and count them up,” I say. He starts doing this. “Separate them by color. I don’t want to touch them.”

When he’s done we tally them up.

0 Reds, 7 Oranges, 5 Yellows, 6 Greens, 4 Blues, 1 Brown.

I tell Eric to turn over the envelope on the seat between us…

Not one to live in wonder for too long, Eric immediately starts dissecting the trick. He eventually settles on…

“All packages must have the same color distribution,’ he says.

“Damn!” I say. “You got me? How did you know? Yes. They all have the exact same colors in them. Red peanut M&Ms are just a myth.”

Realizing that’s probably unlikely to be the case—but unwilling to give it up completely—he hops down the bleacher steps to buy another pack just to test this hypothesis.

This pack has 3 Reds, 7 Oranges, 4 Yellows, 11 Greens, 1 Blue, and 1 Brown. Not only a completely different color distribution but a completely different number of M&Ms.

“Okay. Fuck me. I have no clue,” he says.

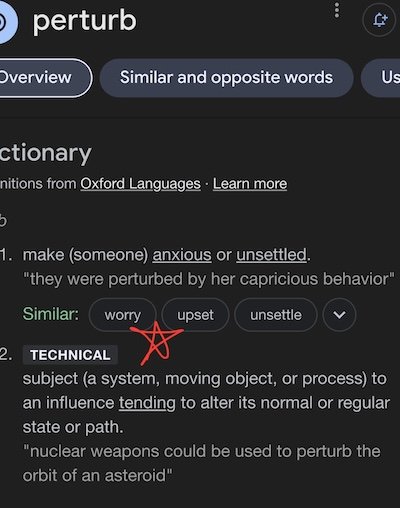

Method

The method is… exactly what you think it is. It’s the subtleties of that method, which I wrote up for last month’s newsletter, that make this what it is. This variation of that trick (on pages 3-7 of the newsletter), allows it to be something you can do when you’re out and about and haven’t asked your spectator to bring anything specific with them. I prefer this presentation, I think. The notion that you can somehow smell the amounts and colors of M&Ms is a more interesting premise than the traditional one that I was writing about there.