What's the Worst Thing About: The MultiNotes App

/For just the fourth time since I made the offer four years ago that someone has taken me up on the offer to discuss the worst thing about a product they’re releasing.

This time it’s the MultiNotes app from Antonio Ferrara.

What Is It?

It’s an app that mimics the iPhone notes app and allows you to use it for up to eight multiple-outs.

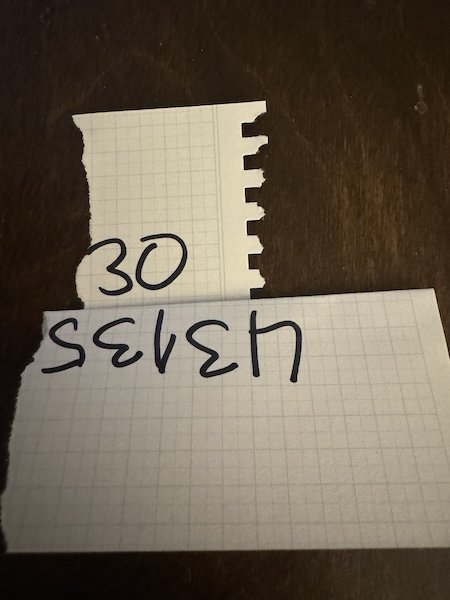

For example (for shitty example), I show you a note in my phone called “The number you’ll name.”

I say: “Name a number between 1 and 8.”

You say two and I open the note and it says:

Then, you begin to worship me as a god.

No, again, that was a simple (and bad) example simply to explain the concept.

The way it works is the note preview is broken up into different sections. Depending on where you tap to open the note, it opens that out for you.

The Good

To my eyes, it looks pretty much just like the real Notes app. (I’ll admit, that I often don’t pick up on it when people say an app looks out of date.)

It’s a true utility app, with endless potential uses.

It’s pretty straightforward to set up new notes/outs, and you can set up an unlimited amount.

You’ll be able to do a number of routines without needing to carry anything else that you don’t usually have with you,

The Bad

It’s iPhone only. (But if you’re an Android user and complaining about this still, move on. Or get an iPhone.)

With 8 outs, it requires a little bit of effort to make sure you’re tapping the preview in the right spot. It’s not difficult. And I haven’t actually ever screwed it up in practice. But you can’t just reach over while they’re holding the phone and tap the note open for them (at least not with 8 outs).

Adding pictures to your notes is (not yet?) possible with the app.

The Worst

Here are two things that could be considered the “worst” thing about MultiNotes.

Everything else being equal, a prediction that’s on your phone is just inherently weaker than the same prediction in hard copy.

While I described the app as having “endless potential uses,” those uses are limited to a 1 in 8 (at most) routine, when this app is used in isolation. It will take some good planning to create a routine that uses this for the sole methodology and has a significant impact on the spectator.

That being said, for me the good far outweighs the bad and I would recommend this to anyone who thinks they might ever have a need for it.

Yes, in my utopia, a prediction trick would end with a physical prediction. But, physical predictions and multiple outs means multiple physical outs. I have to weigh that against the fact that this allows you to do multiple-out effects without having multiple physical predictions. (In fact, it allows you to do multiple multiple-out effects without carrying gimmicked wallets and slips of paper.)

And while I think it’s rare for one-in-a-few effects to be super-powerful by themselves, I think using this as a part of an effect will prove to be very useful. For example, you know I like doing tricks that are supposedly based on instructions for old games and rituals. Being able to change the instructions I need based on something the spectator has said or done can be very useful.

As I play with this some more, I’ll keep you updated on what prove to be the best uses for this. If this app grows a wide user base, like DFB, I think you’ll find a lot of good ideas coming out for it.

More details can be found here.